At some point, collecting books starts to feel like learning.

Shelves fill up. Reading lists grow longer. The visible proof of intellectual ambition is everywhere. And yet, something subtle happens along the way: the more books you own, the less deeply you engage with any single one.

This isn’t a failure of discipline.

It’s a structural problem.

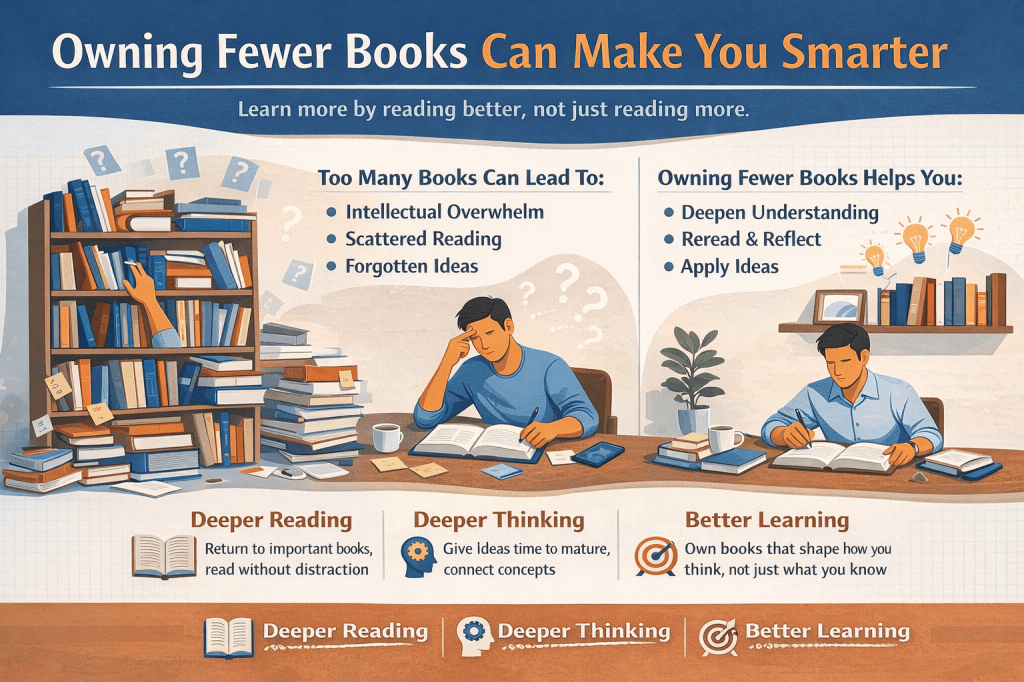

Owning too many books can quietly work against learning. It shifts your identity from reader to collector, from student to consumer of ideas.

If your goal is to learn more from books—not just read more titles—then fewer books may actually make you smarter.

The Problem Isn’t Reading Too Little. It’s Absorbing Too Little.

Most people don’t struggle because they don’t read enough. They struggle because:

- Ideas blur together

- Insights feel fleeting

- Knowledge doesn’t translate into better decisions or behavior

Books get finished, but not integrated.

In response, the instinctive fix is to read more. More titles. More recommendations. More “essential” books. But this often makes the problem worse.

Learning doesn’t scale linearly with volume.

At a certain point, it degrades.

The bottleneck isn’t access to information—it’s attention, reflection, and application.

The Anti-Library Concept (and Why It Matters)

There’s a popular idea, popularized by Nassim Taleb, called the anti-library: a personal library full of unread books that reminds you of how much you don’t know.

That framing is useful as humility. But in practice, most modern anti-libraries don’t inspire learning—they create ambient cognitive pressure.

Every unread book becomes:

- A silent to-do

- A reminder of unfinished intention

- A prompt to move on too quickly

Instead of curiosity, the collection creates anxiety.

The result? Shallower reading, faster skimming, and less synthesis.

The irony is that in trying to surround ourselves with knowledge, we reduce our capacity to digest it.

Reading vs. Collecting: Two Very Different Activities

It helps to separate two behaviors that often get conflated:

- Collecting books is about identity, aspiration, and optionality.

- Learning from books is about attention, friction, and effort.

Collecting is easy. It feels productive. It costs money, not energy.

Learning is slow. It requires rereading, pausing, wrestling with ideas, and sometimes being bored.

When your environment is optimized for collecting, learning becomes optional. When your environment is constrained, learning becomes intentional.

This is why owning fewer books can improve understanding: it forces depth over breadth.

The Hidden Cost of Too Many Books: Attention Fragmentation

Every book you own competes—subtly—for your attention.

Even when they’re not being read, books signal:

- Alternative ideas

- Better arguments

- More urgent insights elsewhere

This creates what you could call intellectual distraction. You’re never fully inside the book you’re reading, because dozens of others are waiting.

The brain responds by:

- Skimming instead of absorbing

- Chasing novelty instead of insight

- Abandoning books at the first moment of friction

Learning, however, lives inside friction.

The most valuable ideas often sit behind pages that are slow, dense, or uncomfortable. Fewer books increase the likelihood that you’ll stay long enough to reach them.

Tsundoku and the Illusion of Future Learning

The Japanese word tsundoku describes the habit of buying books and letting them pile up unread.

It’s often joked about, but it reveals something important: buying a book feels like investing in your future self.

The problem is that this future self is vague. Abstract. Always more disciplined than the present one.

When books pile up, learning gets outsourced to a hypothetical version of you who has more time, energy, and focus.

Owning fewer books collapses that distance. It asks a simple question:

Am I willing to learn this now?

If the answer is no, the book doesn’t belong on your shelf.

Why Constraints Improve Learning

Constraints get a bad reputation, but they’re essential for mastery.

In fitness, fewer exercises lead to better technique.

In finance, fewer goals lead to better outcomes.

In learning, fewer books lead to deeper understanding.

When your reading universe is small:

- You reread more

- You connect ideas across chapters

- You notice nuance instead of headlines

Depth requires returning to ideas. That’s hard to do when you’re constantly tempted by the next book.

Owning fewer books creates a closed loop: the ideas you encounter keep resurfacing until they’re integrated.

The Difference Between Information and Insight

Information is plentiful. Insight is rare.

Information answers questions.

Insight changes how you think.

Insight usually comes from:

- Repetition

- Reflection

- Seeing the same idea from multiple angles over time

This is why rereading one good book can be more valuable than finishing five new ones.

Owning fewer books increases the chance that ideas stick around long enough to transform into insight.

How Owning Fewer Books Changes How You Read

When your shelf is small, your reading behavior changes automatically.

You:

- Read slower

- Highlight more intentionally

- Argue with the author

- Pause to think instead of rushing forward

You’re less likely to abandon a book halfway, because you chose it deliberately.

Scarcity increases commitment.

This isn’t about discipline—it’s about environmental design.

The Anti-Library in Practice: What to Keep, What to Remove

An anti-library isn’t an empty shelf. It’s a curated one.

Here’s a practical framework:

1. Keep books that reward rereading

These are books that:

- Improve with age

- Reveal new layers over time

- Shape how you think, not just what you know

If a book doesn’t get better the second time, it probably won’t change you.

2. Remove books that signal aspiration, not action

If a book has been unread for years, ask:

- Do I still care about this question?

- Am I realistically going to engage with it deeply?

If not, let it go. Releasing it frees attention, not just space.

3. Treat unread books as liabilities

Unread books aren’t neutral. They create cognitive load.

If you keep them, do so intentionally:

- One active “to-read” stack

- Everything else stays out of sight

Better Reading Habits Come From Fewer Choices

Paradoxically, fewer books make it easier to read consistently.

Decision fatigue disappears. There’s no debate about what to read next. The habit becomes automatic.

This mirrors other areas of life:

- Fewer clothes → easier mornings

- Fewer goals → better execution

- Fewer books → deeper learning

The mind thrives when the path is clear.

How to Build Your Own Anti-Library

Think of your anti-library not as a collection, but as a thinking tool.

A simple setup:

- 5–15 physical books you’re actively engaging with

- A short list of books you plan to reread

- Everything else lives digitally or in storage

Digital storage is useful for optionality. Physical space should be reserved for commitment.

If a book earns a place on your shelf, it should earn repeated attention.

Learning Is Not About Exposure. It’s About Assimilation.

Most reading problems aren’t solved by speed, summaries, or productivity hacks.

They’re solved by respecting cognitive limits.

Your mind can only metabolize so many ideas at once. When you exceed that capacity, learning turns into noise.

Owning fewer books respects the natural pace of understanding.

It creates room for:

- Thinking between chapters

- Letting ideas mature

- Applying concepts to real life

That’s where books actually change you.

The Goal Isn’t to Read Fewer Books. It’s to Learn More From Them.

This isn’t an argument against reading widely. It’s an argument against confusing volume with progress.

The smartest readers aren’t the ones who finish the most books. They’re the ones whose thinking is visibly shaped by what they’ve read.

That kind of transformation doesn’t come from accumulation. It comes from attention, time, and return visits.

If owning fewer books helps you do that, then fewer books don’t make you less intellectual.

They make you more intentional.

And intention is where learning begins.

Leave a comment