Most learning fails quietly.

You read a book. It makes sense. You underline a few lines. You close it feeling sharper than before. A week later, you remember the vibe but not the substance. A month later, almost nothing remains.

This isn’t laziness or lack of intelligence. It’s biology.

The real problem is that most people try to fight forgetting, when the smarter move is to use it.

Once you understand the forgetting curve, learning stops being about consumption and starts being about retention, leverage, and long-term payoff.

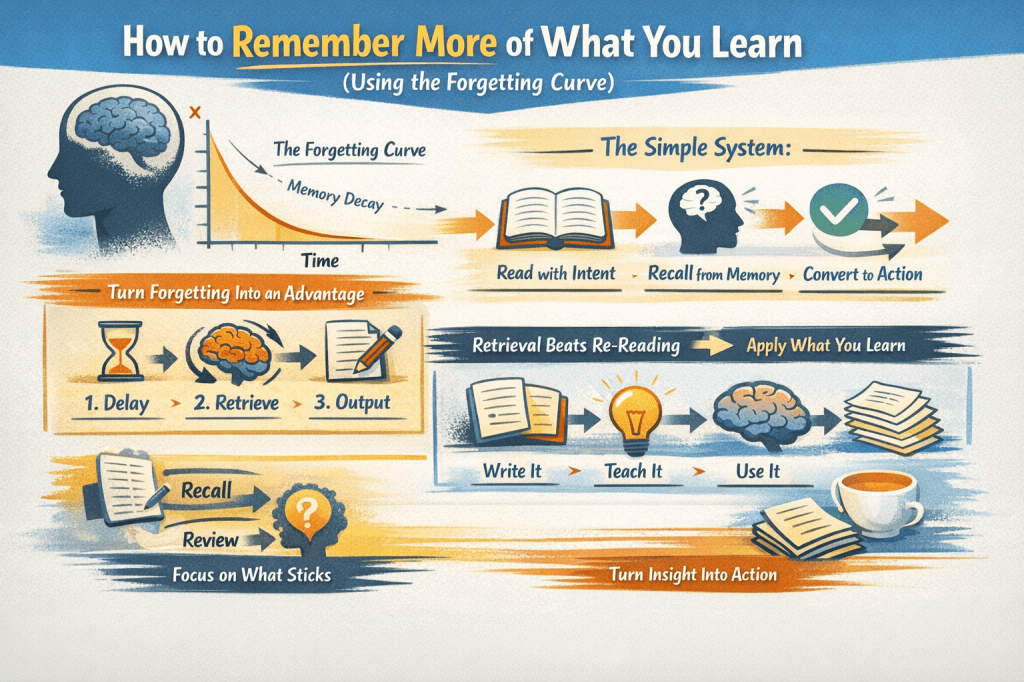

The Forgetting Curve: The Inconvenient Truth About Learning

In the late 19th century, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus ran a series of self-experiments on memory. His conclusion was uncomfortable but clear:

Without reinforcement, we forget most new information rapidly.

The forgetting curve shows that:

- Memory loss happens fastest right after learning

- Forgetting slows over time, but never fully stops

- Passive review barely changes the curve

In practical terms:

- You forget most of what you read within days

- Re-reading helps less than you think

- Highlighting creates the illusion of learning, not durable memory

This isn’t a flaw. It’s an optimization.

Your brain treats memory as a scarce resource. If information isn’t used, recalled, or connected to something meaningful, it gets deleted.

The question is not how to remember everything.

It’s how to signal what’s worth keeping.

Why Most Learning Systems Don’t Work

Modern learning advice is bloated with tools and tactics, but thin on results.

Common approaches fail for predictable reasons:

1. Passive consumption dominates

Books, podcasts, videos, newsletters—easy to consume, hard to retain. Exposure feels productive, but memory requires effort.

2. Notes become graveyards

People take notes faithfully, then never revisit them. Notes without retrieval are just outsourced forgetting.

3. Speed is rewarded over depth

Finishing books, not integrating ideas, becomes the metric. Volume replaces mastery.

4. No feedback loop exists

If learning never changes decisions or behavior, there’s no signal that it mattered.

These systems try to preserve everything, which ironically guarantees that nothing sticks.

The Forgetting Curve Advantage

Here’s the counterintuitive insight most people miss:

Forgetting is not the enemy of learning. It’s the mechanism that makes learning possible.

Memory strengthens when you:

- Allow information to decay slightly

- Attempt recall from memory

- Correct and reinforce

- Repeat this process over increasing intervals

This is why spaced repetition works. But you don’t need flashcards, apps, or complex schedules to apply the principle.

You need three things:

- Delay

- Retrieval

- Output

Used together, they turn forgetting into leverage.

Principle 1: Delay Is a Feature, Not a Bug

Immediate review feels responsible. It’s also inefficient.

When you review something too soon, your brain doesn’t have to work. Recognition kicks in, effort drops, and memory doesn’t strengthen.

Delay creates desirable difficulty.

What to do instead:

- Let hours or days pass before revisiting

- Allow the memory to fade slightly

- Accept discomfort as part of the process

A useful rule:

- If recall feels easy, you reviewed too soon

- If recall feels impossible, you waited too long

- Aim for effortful but possible

That effort is the signal your brain uses to decide: keep this.

Principle 2: Retrieval Beats Re-Reading (Every Time)

Re-reading strengthens familiarity. Retrieval strengthens memory.

This distinction matters.

When you re-read:

- The text does the work

- You recognize ideas instead of reconstructing them

- You mistake fluency for understanding

When you retrieve:

- Your brain rebuilds the idea

- Weak spots are exposed

- Neural pathways strengthen

Practical retrieval methods:

- Write a short summary from memory

- Explain the idea out loud

- Answer a question without notes

- Teach it to someone else

- Sketch the concept on paper

Only after you try should you check the source.

The struggle is not wasted effort. It’s the point.

Principle 3: Output Is the Real Test of Learning

Private learning decays fastest.

If knowledge never leaves your head, it has no stakes, no structure, and no reinforcement.

Output creates friction—and friction creates memory.

Output doesn’t mean publishing. It means externalization.

Examples:

- A paragraph in your own words

- A rule you adopt or reject

- A decision you make differently

- A lens you reuse in other domains

- A short explanation you could give without notes

If learning doesn’t change how you think, decide, or act, it wasn’t learning. It was entertainment.

A Simple Forgetting-Curve Learning System (No Apps)

This system works for books, articles, courses, and even conversations. It scales because it’s selective.

Step 1: Read with intent

Before you start, ask:

- What problem might this help me solve?

- What question am I hoping it answers?

If there’s no answer, don’t read it. Curiosity without intent leads to intellectual clutter.

Step 2: Capture only sharp ideas

While reading, write down:

- Mental models

- Rules of thumb

- Contradictions

- Ideas that challenge your assumptions

Skip summaries. Capture edges, not pages.

If everything feels worth saving, nothing is.

Step 3: Walk away

Do nothing. Let time pass.

Hours, days, or even weeks are fine. This is where forgetting does its filtering.

Step 4: Recall from memory

Without notes, ask:

- What do I remember?

- What stood out?

- What would I explain to someone else?

Struggle first. Then check the source to correct gaps.

Step 5: Convert one idea into output

Take a single idea and turn it into:

- A habit

- A checklist

- A decision rule

- A personal heuristic

- A written insight

One applied idea beats ten vaguely remembered ones.

Why This Beats Traditional Note-Taking

Notes accumulate. Attention doesn’t.

The forgetting-curve approach:

- Forces prioritization

- Filters ideas naturally over time

- Rewards what survives decay

- Prevents intellectual hoarding

If an idea isn’t worth recalling later, it wasn’t worth storing now.

Your brain already understands this. Most learning systems ignore it.

The Hidden Benefit: Better Thinking, Not Just Better Memory

Using forgetting strategically does more than improve recall.

It also:

- Sharpens judgment

- Improves synthesis

- Reduces noise

- Encourages first-principles thinking

When you rely less on stored notes and more on integrated understanding, you stop quoting books and start reasoning from them.

That’s the real upgrade.

Common Objections (And Why They Miss the Point)

“I’ll forget important details.”

You will. That’s fine. Details are cheap. Mental models aren’t.

“This feels slower.”

It is—at first. Long-term retention is faster than re-learning the same thing repeatedly.

“I like having a complete system.”

Completeness is comforting. Effectiveness is better.

Learning is not about preservation. It’s about selection.

The Real Goal: Fewer Ideas, Stronger Integration

Remembering everything is not the goal.

The goal is:

- Fewer concepts

- Deeper understanding

- Faster recall

- Real behavior change

Forgetting is how your brain tells you what matters.

Use it instead of fighting it.

One Final Rule

If you can’t explain an idea a week later without notes, you didn’t learn it—you just encountered it.

Let most things fade.

Strengthen what survives.

That’s how learning compounds instead of evaporates.

Leave a comment