Finishing a book feels like an ending.

In reality, it’s where most reading quietly fails.

The final page is turned, the cover is closed, and within weeks—sometimes days—the ideas dissolve. The excitement fades. The insights blur. The book joins a growing mental pile of “things I once read.”

This isn’t a motivation problem.

It’s a systems problem.

Reading isn’t a single act. It’s a process with an afterlife. And the value of a book is determined far less by how carefully you read it than by what happens after you finish.

Why Most Books Are Forgotten

Forgetting isn’t a personal flaw—it’s the default.

Without reinforcement, recall decays rapidly. Information that isn’t revisited or used becomes inaccessible, no matter how interesting it once felt. This pattern explains why reading more doesn’t necessarily lead to learning more, a dynamic explored in How to Remember More of What You Learn (Using the Forgetting Curve).

There’s also a structural issue.

Most people treat reading as consumption, not integration. The goal becomes finishing books rather than absorbing them. As a result, reading creates a growing backlog of completed material that never shapes thinking or behavior.

Volume increases. Retention doesn’t.

The Two Phases of Reading

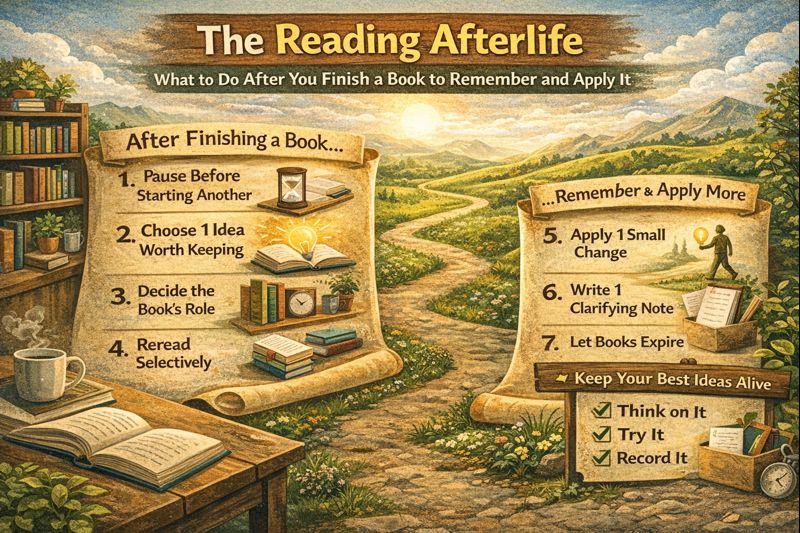

Every book has two distinct phases:

- The reading phase — exposure and comprehension

- The afterlife phase — retention, integration, and application

Most readers invest heavily in the first phase and almost nothing in the second.

That imbalance explains why even excellent books fail to leave a lasting mark. Without an afterlife, reading remains passive. With one, it becomes cumulative.

A practical way to think about this is through the loop described in The Reading Flywheel: How to Remember, Apply, and Learn More From Books: reading feeds reflection, which feeds revisiting, which feeds action, which reshapes how future reading lands.

Step 1: Pause Before Starting the Next Book

The fastest way to forget a book is to immediately replace it with another one.

Momentum feels productive, but cognitively it’s destructive. New inputs overwrite fragile insights from the previous book before they have a chance to stabilize.

Instead, insert a deliberate pause.

Even one day is enough.

Ask:

- What surprised me?

- What challenged my assumptions?

- What idea keeps resurfacing without effort?

This kind of pause mirrors the principle behind Just-in-Time Learning: Why Timing Matters More Than Volume. Reflection at the right moment does more for retention than additional input ever will.

Step 2: Extract One Living Idea

Most people highlight dozens of passages and then move on.

A better approach is ruthless selection.

Choose one idea that feels alive:

- something that reframes a problem you care about

- something that suggests a behavioral shift

- something that refuses to stay abstract

This matters because attention is limited. Carrying too many ideas at once dilutes their impact, a pattern explored in Idea Carrying Capacity: Why Learning Too Much Can Make You Less Effective.

If a book doesn’t leave you with at least one idea worth carrying forward, it was informational—not transformational.

Step 3: Decide the Book’s Role

Not every book deserves the same relationship.

After finishing, decide what role—if any—it should play going forward:

- Reference book: something to consult occasionally

- Seasonal book: worth revisiting at specific life stages

- Practice book: relevant while habits are changing

- One-and-done: useful once, then released

Books don’t need to be permanent to be valuable. Treating every book as lifelong intellectual furniture creates clutter rather than clarity.

This perspective aligns with the idea behind The Reading Compass: How to Choose the Right Book for Every Season of Life: timing matters as much as content.

Step 4: Reread Selectively, Not Automatically

Rereading works—but not the way most people expect.

The value of rereading isn’t repetition. It’s layering. On a second pass, different ideas surface because you’re no longer reading as a beginner. Context has changed.

This is why selective rereading is so effective, as described in Learning in Layers: Why Rereading Books Unlocks Deeper Insights.

Useful approaches include:

- revisiting marked passages

- rereading a single chapter months later

- returning when circumstances change

Full cover-to-cover rereads should be rare and intentional.

Step 5: Turn Reading Into a Light Practice

The most reliable way to remember a book is to use it.

Not dramatically. Not perfectly. Light application is enough:

- test one idea for two weeks

- adjust one habit slightly

- explain the concept to someone else

Reading that never touches behavior fades quickly. Reading that shapes even small actions sticks.

This is the difference between books that inform and books that change you—a distinction explored in How to Read Books That Change You — Not Just Inform You.

Step 6: Write Less, But Write Better

Many readers feel pressure to take extensive notes.

This often backfires.

Writing should clarify thinking, not archive it. Dense notes that are never revisited create the illusion of learning without retention.

More effective alternatives:

- one paragraph summarizing the core idea

- one sentence capturing what changed in your thinking

- one question the book left unresolved

Writing in this way turns reading into dialogue rather than documentation, a practice explored in Marginalia Magic: How Writing in Books Improves Comprehension and Critical Thinking.

Step 7: Let Books Expire

Most books are not meant to stay relevant forever.

Holding onto every idea creates intellectual clutter. Knowing when to let a book fade is a skill.

Curated forgetting matters as much as remembering. Owning fewer mental commitments often leads to deeper understanding, a theme explored in How to Learn More From Books: Why Owning Fewer Books Can Make You Smarter.

The goal isn’t to remember everything you read.

It’s to remember what matters now.

When Reading Becomes Avoidance

Reading can quietly turn into a sophisticated form of procrastination.

When books replace:

- decision-making

- experimentation

- action

…learning stalls.

This doesn’t mean reading is the problem. It means the loop is incomplete. Insight without application decays. Integration requires friction.

Closing that loop is what separates reading as entertainment from reading as growth.

A Simple Reading Afterlife Checklist

After finishing a book:

- Pause before starting the next one

- Identify one meaningful idea

- Decide the book’s role

- Reread selectively if useful

- Apply one small change

- Write one clarifying note

- Release the rest

This turns reading into a sustainable system instead of a consumption habit.

The Real Goal of Reading

The goal isn’t completion.

It’s transformation.

The books that matter most aren’t the ones you finish fastest or quote most often. They’re the ones that quietly reshape how you think, decide, and act—long after the final page.

That happens in the reading afterlife.

If you want books to change you, don’t measure how many you’ve read.

Ask what’s still alive from the last one.

Leave a comment