Frugality is powerful because it compounds.

Spend less than you earn, invest the difference, repeat—and over time, small decisions snowball into financial independence. This logic is sound. It’s also incomplete.

Because every optimization has side effects. And past a certain point, frugality doesn’t just save money—it quietly starts to cost time, energy, health, relationships, and even long-term wealth.

These costs don’t show up in spreadsheets. They appear one step later, as second-order effects.

Understanding them is what separates sustainable financial independence from burnout disguised as discipline.

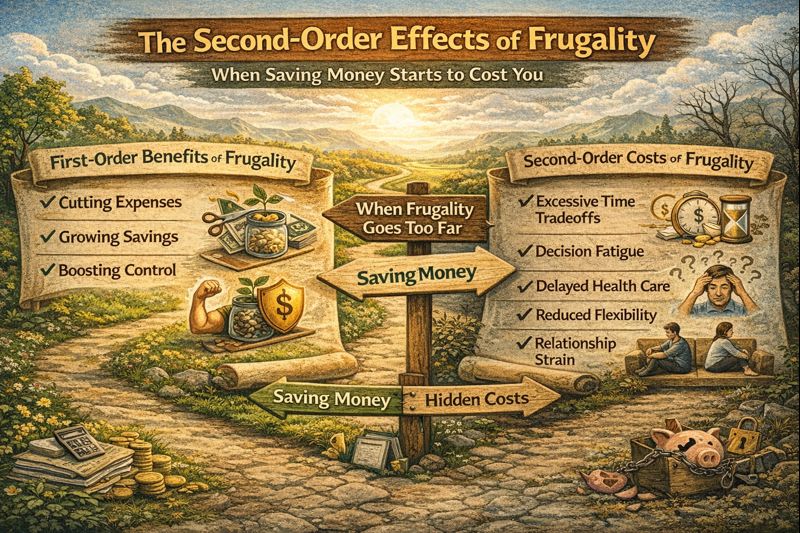

First-Order vs Second-Order Effects

A first-order effect is immediate and obvious:

- Cooking at home saves money

- Living in a smaller apartment lowers rent

- Cutting subscriptions reduces monthly expenses

A second-order effect is indirect and delayed:

- Cooking every meal increases cognitive load and decision fatigue

- A cramped living space affects sleep, focus, and mood

- Eliminating small conveniences increases friction across your day

Frugality looks clean and rational at the first order. The second order is where it gets messy.

This is why many people feel financially “ahead” on paper but perpetually exhausted in real life—a mismatch explored in Why FIRE Isn’t Sustainable Without Financial Slack.

The Optimization Trap

Frugality often starts with high-leverage changes:

- Automating savings

- Cutting obvious waste

- Aligning spending with values

These changes feel empowering. They reduce stress and increase control.

But then something subtle happens.

You keep optimizing—not because it matters, but because you’ve trained yourself to notice inefficiency everywhere.

You comparison-shop endlessly.

You track micro-expenses.

You hesitate over purchases that would meaningfully improve your quality of life.

At this stage, frugality stops being a strategy and becomes an identity.

And identities resist stopping.

Second-Order Effect #1: Time Becomes Invisible

Extreme frugality often trades money for time—but time doesn’t show up on a balance sheet.

Examples:

- Driving across town to save a few dollars

- Managing multiple bank accounts for marginal yield

- DIY projects that sprawl into weekends

Individually, these choices seem rational. Collectively, they fragment your attention.

This is a form of time arbitrage failure, where the pursuit of small savings crowds out higher-value uses of time—learning, rest, creativity, or earning more. The trade-off mirrors patterns described in Time Arbitrage: How Flexible Schedules Help You Save More, Spend Less, and Build Wealth.

Money compounds best when paired with focus. Frugality that erodes focus undermines its own goal.

Second-Order Effect #2: Cognitive Load Accumulates

Every decision has a cost.

When frugality expands into constant optimization, it multiplies daily decisions:

- Is this the cheapest option?

- Can I delay this purchase?

- Is there a better deal elsewhere?

Decision fatigue doesn’t announce itself. It shows up as:

- Reduced patience

- Slower thinking

- Avoidance of complex but important decisions

Ironically, this often leads to worse financial outcomes—missed opportunities, delayed investing, or paralysis around meaningful upgrades.

This pattern parallels what happens in learning when intake exceeds integration, discussed in Idea Carrying Capacity: Why Learning Too Much Can Make You Less Effective.

More optimization isn’t always more intelligence. Sometimes it’s just more noise.

Second-Order Effect #3: Health Becomes a Line Item

One of the most expensive forms of frugality is underinvesting in health.

It rarely looks dramatic at first:

- Skipping recovery because it feels “non-essential”

- Choosing cheaper food at the expense of quality

- Avoiding preventive care because nothing feels wrong yet

These decisions save money now and cost far more later.

Health is a compounding asset. Neglect shows up slowly, then all at once—a dynamic explored across The Minimum Effective Longevity Habits and Training for Longevity.

Frugality that degrades health is a negative-return investment, no matter how disciplined it feels.

Second-Order Effect #4: Optionality Shrinks

The goal of financial independence isn’t just lower expenses—it’s better choices.

Extreme frugality can paradoxically reduce optionality:

- Reluctance to spend on skill-building

- Avoidance of travel that expands perspective

- Hesitation to invest in environments that support growth

When every expense is treated as a leak, opportunities start to look like threats.

This runs counter to the idea behind The Optionality Playbook: Why Financial Independence Is About Better Choices, Not Early Retirement. Money is leverage. Hoarding it at the expense of life flexibility defeats the purpose.

Second-Order Effect #5: Relationships Absorb the Friction

Money decisions are rarely isolated.

When frugality becomes rigid:

- Social plans are declined

- Shared experiences are downgraded

- Generosity becomes uncomfortable

Over time, this creates subtle distance. Not because of money itself, but because of the emotional friction around it.

Relationships are another compounding asset. Like health, they don’t respond well to optimization-by-deprivation.

When Frugality Compounds — and When It Backfires

Frugality works best when it:

- Eliminates low-value spending

- Reduces recurring stress

- Frees attention for meaningful goals

It backfires when it:

- Increases friction across daily life

- Consumes disproportionate mental energy

- Prevents investment in health, skills, or relationships

This distinction echoes the core argument in Expense Ratios for Life: When Frugality Compounds — and When It Backfires.

The problem isn’t frugality. It’s failing to update it as circumstances change.

The Role of Financial Slack

Slack is excess capacity.

In finances, slack looks like:

- Cash buffers

- Slightly higher spending than the minimum

- Redundancy in systems

Slack isn’t waste. It’s resilience.

Without slack, every unexpected expense feels like a failure. With slack, small shocks don’t require emotional or cognitive recovery.

This is why sustainable FIRE paths prioritize margin, not maximization—a theme developed in Financial Independence Without Extremes.

A Simple Test: Is This Optimization Still Paying Rent?

Before optimizing further, ask:

- Does this save meaningful money?

- Does it reduce stress or increase it?

- Would I recommend this habit to someone starting from scratch?

If an optimization wouldn’t make the “first page” of advice, it probably shouldn’t live permanently in your system.

Frugality as a Phase, Not a Permanent State

Early in the FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) journey, aggressive frugality often makes sense. The leverage is high. Progress is visible. Habits form quickly.

Later, the same tactics deliver diminishing returns.

At that point, the goal shifts:

- from minimizing spending → to maximizing life quality per dollar

- from control → to calibration

- from efficiency → to sustainability

This mirrors transitions seen in other domains—training, learning, travel—where intensity must evolve to avoid plateau or injury.

Redefining “Enough”

The hardest part of frugality isn’t starting.

It’s stopping.

Stopping requires redefining success. Not as the lowest possible expense line, but as a life that feels spacious, resilient, and aligned.

This reframing sits at the heart of The Psychology of Enough: How to Redefine Wealth Beyond Money.

Enough isn’t complacency. It’s clarity.

Frugality That Actually Scales

Sustainable frugality looks like:

- High savings rate from big decisions, not constant micro-optimizations

- Spending freely on what compounds health, energy, and skill

- Letting go of savings tactics that no longer move the needle

In other words, frugality becomes strategic, not obsessive.

The Real Cost of Saving Money

Money saved at the expense of:

- health

- time

- focus

- relationships

- optionality

…isn’t truly saved.

It’s deferred cost.

The purpose of frugality isn’t to win a spreadsheet. It’s to build a life that feels lighter, not tighter, as you move toward independence.

Knowing when to stop optimizing is itself a financial skill.

Leave a comment