Modern life is not physically demanding—but it is physically unnatural.

Most of us sit for hours, stare at screens, move in narrow ranges, and live indoors. We work with our hands in front of us, our eyes fixed at arm’s length, and our bodies largely still. None of this is catastrophic in isolation. The problem is exposure. Day after day, year after year, the same small stresses accumulate quietly.

The result isn’t sudden illness or obvious breakdown. It’s slower and easier to ignore: stiffness that becomes chronic, energy that never fully returns, recurring aches that never quite heal. This is the same slow-burn dynamic I’ve written about in The Hidden Injuries of Sitting All Day and Digital Posture: How Screens Reshape Your Body — not dramatic failure, but gradual loss of capacity.

This article isn’t about peak fitness, aesthetics, or pushing limits. It’s about tolerance: designing a body that can handle modern life without constant maintenance, pain, or recovery cycles.

The core issue: Mismatch, not Laziness

Most people don’t have a motivation problem. They have a design problem.

Our bodies evolved for:

- Frequent low-intensity movement

- Occasional high-intensity effort

- Wide ranges of motion

- Long periods of standing, walking, squatting, and carrying

Modern life delivers the opposite:

- Prolonged sitting

- Fixed postures

- Repetitive micro-movements (keyboard, mouse, phone)

- Artificial light and disrupted sleep cues

Even people who “work out” regularly spend 8–10 hours a day in positions their bodies aren’t built to tolerate. A 60-minute gym session doesn’t cancel out nine hours of stillness—just like a single healthy meal doesn’t undo a week of poor nutrition.

This is why many active people still deal with back pain, tight hips, shoulder issues, and low-grade fatigue. As I discussed in Why Systems Beat Motivation, the issue isn’t effort—it’s exposure and structure.

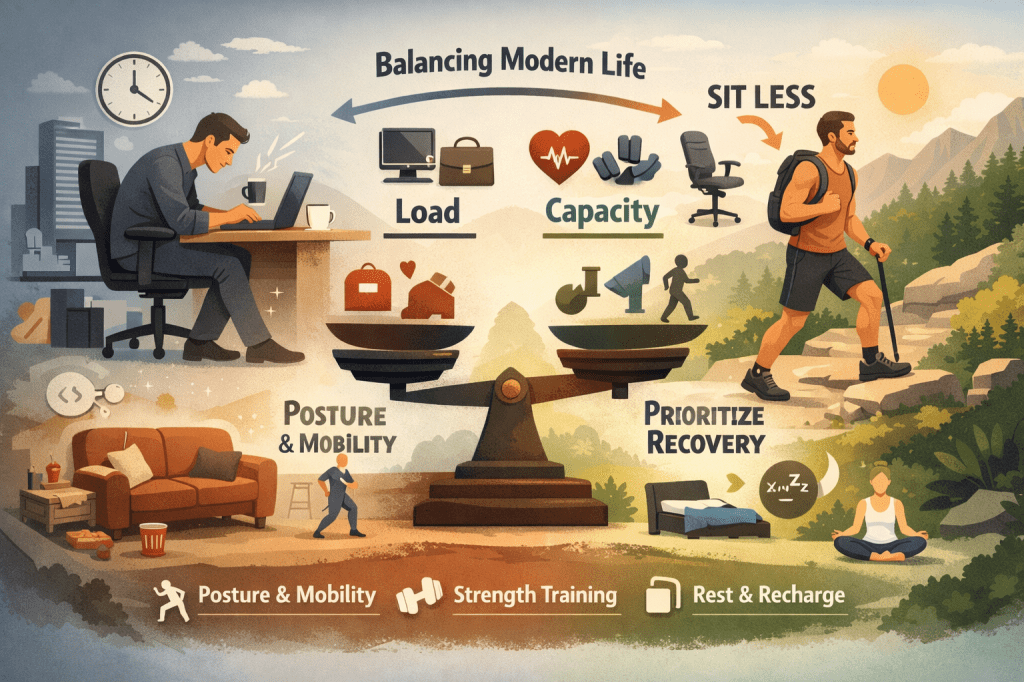

Load vs Capacity: A Better Mental Model

A useful way to think about physical health is load versus capacity.

- Load is what modern life demands of your body: sitting, screens, stress, travel, poor sleep.

- Capacity is what your body can tolerate without pain, fatigue, or injury.

Problems arise when load exceeds capacity—not suddenly, but cumulatively. Small stresses that never fully resolve eventually become chronic issues.

Most people try to reduce load by optimizing their environment:

- Better chairs

- Standing desks

- Ergonomic keyboards

These help, but they’re incomplete. You can’t ergonomics your way out of low physical capacity.

The more robust solution is to increase capacity—so the same environment places less strain on your system. This mirrors financial resilience: just as financial slack matters more than perfect budgeting (as explored in Why FIRE Isn’t Sustainable Without Financial Slack), physical slack matters more than perfect posture.

The Four Capacities a Modern Body Needs

To tolerate a sedentary, screen-based world, your body needs sufficient capacity in four areas.

1. Postural Endurance

You don’t need perfect posture. You need the ability to hold imperfect posture without breakdown.

Modern work requires sustained positions. Postural endurance comes from:

- A strong upper back

- Endurance in the deep neck flexors

- Core stability under low load

This is why two people can sit at the same desk all day and have very different outcomes. One accumulates strain; the other tolerates it. I’ve explored practical ways to build this in Posture, Breath, and Walking.

2. Joint Range and Control

Modern life narrows movement.

Hips stop extending. Shoulders stop rotating. Ankles stiffen. When joints lose range, stress shifts elsewhere—often to the lower back, neck, or knees.

You don’t need extreme flexibility. You need:

- Sufficient range of motion

- Control at the end ranges

This is the foundation of durability. It’s also why daily mobility work, as discussed in Daily mobility for joint health, pays dividends over decades.

3. General Strength

Strength is not about lifting heavy—it’s about margin.

A stronger body:

- Absorbs stress better

- Fatigues more slowly

- Gets injured less often

Think of strength as a buffer. Just as financial buffers create optionality, physical strength creates resilience. You don’t need maximal strength; you need adequate strength everywhere. This philosophy aligns with the approach in Training for Longevity: How to Exercise for Long-Term Health, Not Just Looks.

4. Recovery Capacity

Screens, cognitive load, and constant stimulation tax the nervous system.

Without adequate recovery, even modest physical demands feel overwhelming. Sleep, breathing, and downregulation aren’t optional—they are structural supports. I’ve written about this directly in Recovery Is a Skill and The Sleep Efficiency Blueprint.

Designing a Body for Sedentary Reality

Instead of trying to “undo” sitting, aim to increase tolerance.

Move Frequently, Not Heroically

Frequency beats intensity.

- Stand up every 30–60 minutes

- Walk between tasks

- Add short movement breaks

These movements don’t need to be impressive or sweaty. They restore circulation, reset tissues, and reduce stiffness. Think of them as maintenance, not workouts—similar to the idea behind Movement Snacks.

Train the Positions Modern Life Avoids

Modern life minimizes:

- Deep hip flexion

- Overhead shoulder movement

- Rotation and lateral movement

Training should reintroduce these patterns safely:

- Squats and split squats

- Rows and overhead presses

- Carries and rotational work

The goal isn’t athletic performance—it’s keeping these movement options available as you age. This is especially important if you travel often, as discussed in Travel Warm-Ups and Comfort-Optimized Travel.

Build Strength for Endurance, Not Records

Low to moderate loads, controlled reps, and consistency matter more than personal records.

You’re training for:

- Long workdays

- Travel fatigue

- Decades of use

This mirrors sustainable FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) principles: extreme intensity works briefly, but sustainable systems win long-term. Strength you can maintain year-round beats cycles of burnout.

Treat Mobility Like Hygiene

Mobility isn’t something you save for later.

It’s closer to brushing your teeth:

- Short

- Frequent

- Preventive

Five to ten minutes a day compounds dramatically over years. This is the same compounding logic explored in The minimum effective longevity habits.

Screens Affect More Than Posture

Screen use doesn’t just change how you sit—it affects your entire system.

Extended screen time influences:

- Breathing patterns

- Eye strain and headaches

- Nervous system tone

A body designed for modern life needs:

- Occasional gaze shifts to distance

- Nasal breathing under low stress

- Regular breaks from stimulation

These aren’t wellness luxuries. They directly influence muscle tension, recovery, and long-term comfort—topics I explored further in Your Body’s Dashboard.

The Goal isn’t Optimization—It’s Durability

A tolerant body is not perfectly aligned, endlessly energized, or pain-free at all times.

It’s resilient.

It can:

- Sit when required

- Move when asked

- Travel without falling apart

- Absorb stress without constant injury

This is a different goal than aesthetics or performance. It’s quieter, but far more valuable—especially as you age.

A Simple Starting Framework

If you do nothing else:

- Interrupt sitting frequently

- Strength train 2–3 times per week

- Move joints daily through comfortable ranges

- Protect sleep and recovery

You don’t need perfection. You need consistency.

Final Thought

Modern life isn’t going to become less sedentary or less screen-based.

The realistic strategy isn’t to fight it—it’s to adapt to it.

Design a body with enough capacity to tolerate the world you actually live in.

That’s not lowering standards. It’s designing for reality—and for the long run.

Leave a comment