We live in the most information-rich environment in human history.

Books, podcasts, newsletters, feeds, courses, threads, videos—answers are always one click away. Learning has never been easier. And yet many people feel mentally scattered, overwhelmed, and oddly stagnant despite consuming more information than ever.

They read constantly but struggle to remember.

They learn a lot but apply very little.

They feel informed—but not clearer.

This isn’t a discipline problem.

And it isn’t a motivation problem.

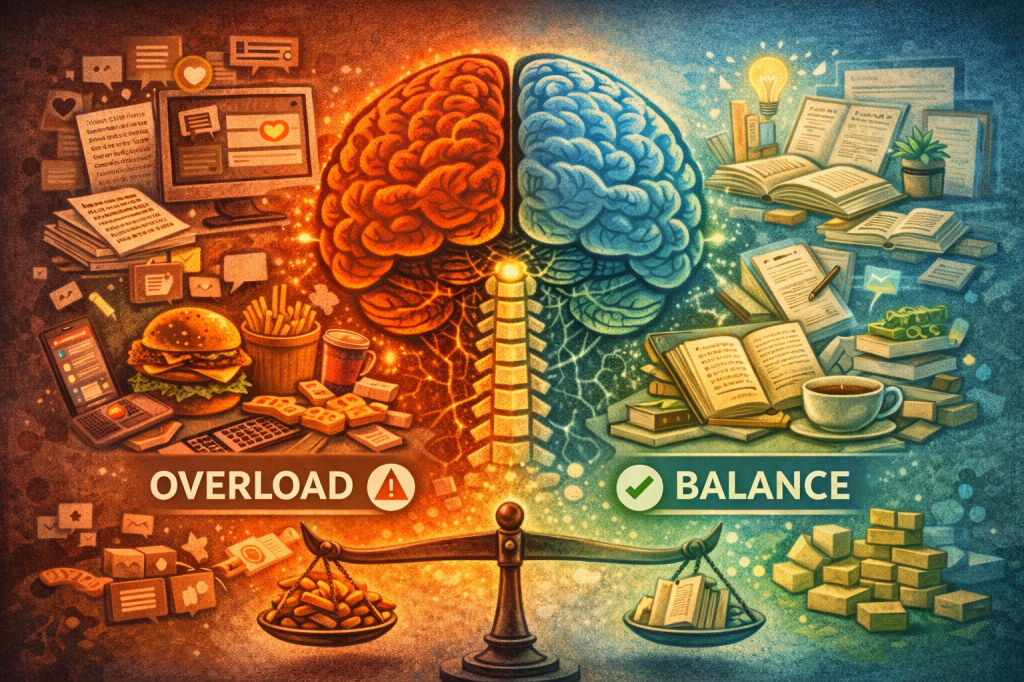

It’s a nutrition problem.

Just as eating more food doesn’t guarantee better health, consuming more information doesn’t guarantee better thinking. What matters—often more than volume—is quality, timing, and digestion.

In other words: cognitive nutrition.

Information is fuel, not a hobby

We tend to treat information as entertainment or identity.

“I’m someone who reads a lot.”

“I listen to podcasts constantly.”

“I’m always learning.”

But information isn’t neutral. It shapes perception, decision-making, attention, and energy. It either supports clear thinking—or quietly degrades it.

This mirrors a pattern I’ve written about before in Idea Carrying Capacity: How Many Concepts Can You Actually Use at Once. The brain has limits. Beyond a certain point, more input doesn’t lead to growth—it leads to congestion.

Nutrition is a useful metaphor here because it forces a more honest question:

Is this information nourishing—or just filling?

Quantity became the default because it was easy

Historically, information was scarce. Access itself was valuable.

Today, access is trivial. Filtering is the real skill.

Algorithms reward volume. Productivity culture celebrates consumption. “Read more” became shorthand for “get smarter,” even though the two are only loosely correlated.

The result is the intellectual equivalent of ultra-processed food:

- easy to consume

- engineered to be stimulating

- low in lasting value

You feel busy and engaged—but not strengthened.

This dynamic shows up repeatedly in modern learning. In Just-in-Time Learning: Why Timing Matters More Than Volume, I explored how information consumed too early or too broadly often decays before it can be used. Cognitive nutrition isn’t just about what you consume—it’s about when and why.

The hidden cost of low-quality information

Poor cognitive nutrition doesn’t usually feel bad immediately.

Instead, it shows up indirectly:

- shallow understanding

- decision fatigue

- reduced attention span

- constant sense of “falling behind”

These aren’t signs of low intelligence. They’re signs of overfed but undernourished cognition.

Mental junk food has predictable effects

Low-quality information tends to:

- prioritize novelty over depth

- fragment attention

- trigger emotional reactions without resolution

- provide opinions instead of frameworks

Information that doesn’t integrate into existing mental models becomes mental noise.

Over time, this noise reduces your ability to think clearly—much like chronic poor diet reduces physical resilience.

Why more information often reduces understanding

Understanding requires integration, not exposure.

The brain learns by:

- connecting new ideas to existing structures

- revisiting concepts across time

- applying ideas in different contexts

But high-volume consumption crowds out these processes.

In The Learning Bottleneck: Why Smart People Plateau, I explored how intelligent, curious people often stall—not because they lack information, but because they never slow down enough to consolidate it.

Cognitive nutrition reframes the problem:

Learning doesn’t fail because you didn’t eat enough.

It fails because you never digested what you consumed.

Quality information has specific characteristics

High-quality cognitive input tends to share a few traits:

1. It Changes How You See, Not Just What You Know

The best books and essays don’t add facts—they reshape mental models.

This is why some ideas stay with you for years while others vanish in days. I explored this distinction deeply in How to Read Books That Change You — Not Just Inform You.

Good cognitive nutrition alters perception. It reduces future confusion rather than adding more content to manage.

2. It Has a Long Half-Life

Quality information remains useful across time and context.

Frameworks age better than tactics. Principles outlast trends. This is why rereading matters—a theme I explored in Learning in Layers: Why Rereading Books Unlocks Deeper Insights.

Low-quality information decays quickly, requiring constant replenishment. High-quality information compounds.

3. It Demands Effort (and Rewards It)

Just as nutritious food is often less hyper-palatable, nourishing ideas usually require more cognitive work.

They may:

- feel slow to read

- challenge existing beliefs

- resist easy summarization

This “effort tax” is a feature, not a bug. It signals that the brain is being trained, not entertained.

Information overload is a design problem, not a willpower problem

Most people blame themselves for feeling overwhelmed.

“I need better discipline.”

“I should read less.”

“I should take more notes.”

But overload is usually a system failure, not a personal one.

In Why Systems Beat Motivation, I argued that outcomes improve when environments are designed correctly. Cognitive nutrition works the same way.

If your information environment constantly pushes novelty, urgency, and volume, your brain will respond accordingly.

Willpower cannot outpace a broken diet.

From consumption to allocation

A useful shift is to stop thinking about information as something you consume and start thinking about it as something you allocate.

This mirrors my framing in Learning Like an Investor: How to Allocate Attention for Long-Term Growth.

An investor doesn’t chase every opportunity. They allocate capital deliberately, based on expected return and risk.

Cognitive nutrition asks:

- What information deserves your limited attention?

- What has compounding value?

- What merely creates mental churn?

The role of constraints in better thinking

Interestingly, many people report clearer thinking when they:

- read fewer books

- follow fewer voices

- reduce input volume

This isn’t accidental.

Constraints force selectivity. Selectivity improves digestion.

I explored this in How to Learn More From Books: Why Owning Fewer Books Can Make You Smarter. Scarcity—when chosen intentionally—improves focus and depth.

Just as elimination diets clarify physical reactions, information reduction clarifies thinking.

Cognitive nutrition across life domains

Poor cognitive nutrition doesn’t stay confined to learning. It spills into:

- Decision-making: more opinions, less judgment

- Productivity: constant input, little output

- Well-being: persistent mental restlessness

This mirrors patterns I’ve identified in other domains:

- financial overload (The Psychology of Enough)

- travel overload (Why Repeating Destinations Beats Chasing New Ones)

- lifestyle overload (Future-Proofing Your Lifestyle)

Across domains, the lesson is consistent: more options reduce satisfaction unless filtered well.

Designing a high-quality information diet

Cognitive nutrition isn’t about consuming less information. It’s about consuming better information—at the right time, in the right amount.

A few high-level principles emerge:

Prioritize depth over breadth

Revisit ideas. Reread. Apply. Let concepts mature.

Match information to immediate use

This reinforces Just-in-Time Learning and reduces decay.

Create digestion space

Reflection, writing, and discussion are part of learning—not optional extras.

Treat attention as finite

I’ve framed this repeatedly as an energy problem (Energy Management vs Time Management). Information consumes energy too.

The long-term payoff of better cognitive nutrition

When information quality improves, subtle but meaningful shifts occur:

- decisions feel simpler

- thinking becomes calmer

- learning compounds instead of resets

- confidence comes from judgment, not volume

You stop feeling behind. Not because you know everything—but because you trust what you know.

Less information, better thinking

Cognitive nutrition isn’t about asceticism or intellectual minimalism.

It’s about respect—for your brain’s limits, your attention, and your time.

In a world that rewards constant consumption, choosing quality over quantity is a quiet competitive advantage. Not just for learning—but for clarity, focus, and long-term growth.

Your brain doesn’t need more food.

It needs better meals.

Leave a comment