Reading is one of the highest-leverage habits available to a knowledge worker.

It exposes you to ideas you might never encounter otherwise. It compresses decades of experience into a few focused hours. It sharpens language, expands mental models, and provides a steady stream of insight.

And yet, many people who read constantly feel stuck.

They read more books every year, but their thinking doesn’t feel clearer. Their decisions don’t improve proportionally. Their understanding remains shallow, brittle, or borrowed. They can recognize good ideas—but struggle to generate their own.

This isn’t a failure of discipline or intelligence. It’s a misunderstanding of how thinking actually improves.

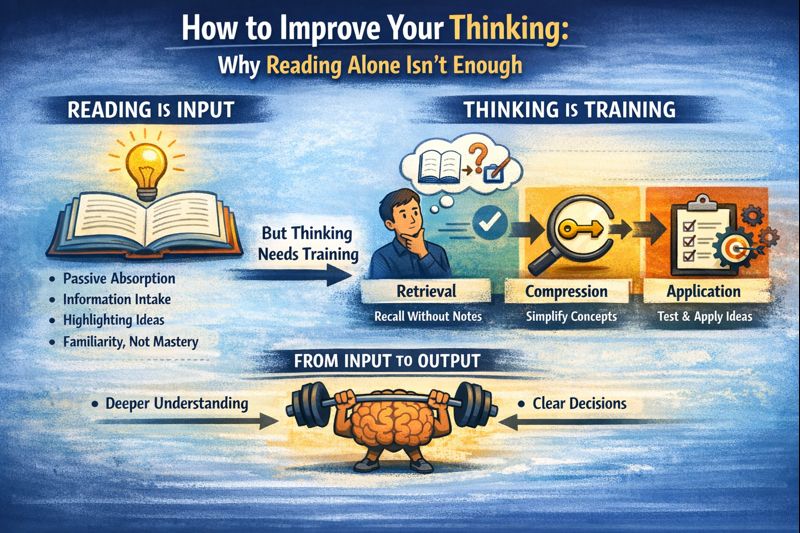

Reading is input. Thinking is a trained skill.

And like any skill, it requires resistance, feedback, and recovery—not just volume.

Reading Builds Input. Thinking Requires Training.

Reading supplies structure for you.

The author has already done the hard work: selecting examples, resolving contradictions, smoothing complexity into a narrative. When you read, your brain follows along on rails. This is efficient—but efficiency is not the same as growth.

Thinking, by contrast, is what happens when:

- the structure is removed

- the conclusion isn’t obvious

- the answer isn’t supplied

- the idea has to survive real-world constraints

Two people can read the same book and walk away with radically different outcomes. One accumulates information. The other integrates understanding.

The difference isn’t how much they read.

It’s what they do after reading.

The Illusion of Progress From Reading

Reading creates a powerful illusion of progress.

You’re engaged. You’re highlighting. You’re nodding along. Ideas feel familiar, even obvious. This sense of fluency is comforting—and misleading.

Psychologically, recognition feels like understanding. But recognition is passive. Understanding is active.

This illusion is especially dangerous for smart, curious people. The faster you read and the more you consume, the easier it becomes to confuse familiarity with mastery.

Common signs of this trap:

- You can summarize ideas but struggle to apply them

- Your opinions sound polished but generic

- You forget most of what you read within weeks

- You feel “informed” but not clearer

None of this means reading is bad. It means reading alone is incomplete.

Thinking Is a Skill With Load Requirements

Every skill improves under load.

Muscle requires resistance. Cardiovascular fitness requires sustained effort. Even mobility improves only when joints move under controlled stress.

Thinking is no different.

Your thinking improves when your mind is forced to:

- hold ideas without external support

- reconcile conflicting concepts

- explain something clearly without notes

- make decisions under uncertainty

Reading removes load. It supplies clarity instead of demanding it.

To improve thinking, you need deliberate friction—the mental equivalent of resistance training.

Why Reading More Eventually Stops Helping

Early on, reading delivers huge gains.

You’re filling gaps. Learning basic frameworks. Expanding vocabulary and perspective. But over time, the returns diminish.

Eventually, the bottleneck is no longer access to information.

It’s processing capacity.

This is why:

- reading faster doesn’t help

- reading more books doesn’t help

- better note-taking apps don’t help

At a certain point, thinking—not learning—becomes the constraint.

The Three Components of Thinking Fitness

Improved thinking doesn’t require complex systems or productivity tools. It requires a shift from consumption to training.

Three practices matter more than everything else.

1. Retrieval: Thinking Without the Book Open

Most people never test whether they actually understand what they read.

A simple rule applies:

If you can’t explain it without looking, you don’t own it.

Retrieval forces your brain to reconstruct ideas from memory. This process feels uncomfortable because it exposes gaps—and that discomfort is the signal that learning is happening.

Simple retrieval practices:

- Write a summary from memory

- Explain the idea out loud as if teaching it

- Ask: What problem does this solve? Why does it matter?

Retrieval strengthens understanding far more than rereading or highlighting ever will.

2. Compression: Reducing Ideas to Their Essence

Thinking improves when complexity is compressed into clarity.

Compression requires judgment:

- What’s essential?

- What’s supporting detail?

- What can be discarded?

Anyone can quote a passage. Fewer people can reduce a chapter to a paragraph—or a paragraph to a sentence.

Compression exercises:

- Summarize a book in five bullets

- Reduce an idea to one mental model

- Explain it using a real-world analogy

Compression transforms information into something usable.

3. Application: Stress-Testing Ideas in Reality

Ideas only become intelligent when they survive contact with reality.

Until an idea is applied—financially, physically, socially, or professionally—it remains theoretical. Application introduces friction, trade-offs, and unintended consequences.

This is where thinking actually sharpens.

Useful questions:

- Where could this fail?

- What assumptions does this rely on?

- How would this change my behavior next week?

Even small experiments force ideas to adapt to constraints. That adaptation is where insight lives.

Why Smart Readers Plateau

Many intelligent readers hit a plateau not because they lack ability, but because they never shift modes.

They stay in input mode long after the problem becomes integration.

They keep adding ideas when the real work is subtracting, refining, and testing.

This is why rereading often produces deeper insight than novelty. Familiar ideas, revisited under new conditions, reveal layers that weren’t visible before.

Depth compounds. Novelty resets.

Thinking Happens Between Books

The most valuable thinking rarely happens while reading.

It happens:

- during pauses

- in unfinished thoughts

- when contradictions are left unresolved

- weeks later, when an idea resurfaces unexpectedly

This is why constant consumption can actually weaken thinking. It leaves no space for digestion.

Thinking fitness improves when you intentionally slow the input and increase the load per idea.

A Simple Thinking Fitness Protocol

You don’t need a system. You need friction.

After finishing something worth reading:

- Close the book

- Write what you remember (no checking)

- Reduce it to one core principle

- Identify one real-world application

- Revisit it a week later

Do this with just one piece of content per week and your thinking will improve faster than reading ten books passively.

Reading Is the Warm-Up, Not the Workout

Reading opens the door. It doesn’t walk you through it.

If your goal is sharper judgment, clearer decisions, and deeper understanding, treat ideas the way athletes treat training:

- apply load

- recover

- revisit

- adapt

The goal isn’t to read more.

The goal is to think better with less.

And that happens not while the book is open—but after it closes.

Related Reading

If this article resonated, you may also enjoy these related pieces:

Learning, Reading, and Thinking

- Learning Like an Investor: How to Allocate Attention for Long-Term Growth

- The Learning Bottleneck: Why Smart People Plateau (And How to Break Through)

- Idea Carrying Capacity: How Many Concepts Can You Actually Use at Once?

- How to Remember More of What You Learn (Using the Forgetting Curve)

- The Reading Flywheel: How to Remember, Apply, and Learn More From Books

- How to Understand Any Book Better: The 3-Pass Reading System Explained

- Why Some Books Change Your Thinking (and Others Don’t)

- Just-in-Time Learning: Why Timing Matters More Than Volume

Systems, Focus, and Cognitive Load

- Cognitive Nutrition: Why Information Quality Matters More Than Quantity

- Energy Management vs Time Management: How to Increase Focus and Avoid Burnout

- Why Systems Beat Motivation: A Practical Framework for Health, Wealth, and Learning

Leave a comment